Dear Anne:

I fell in love first with your confessions. You died years before I was born, and it would be years still before I grew into a suburban teenager who felt at a loss to describe the world around her.

Never mind the world inside her.

But there you were, beautiful, your “long brown legs,/ sweet dears, as good as spoons;” messy and bloody and searching. My friend Sarah found you first, and then handed on your legacy. Suddenly, I didn’t feel so alone. Your Complete Poems, published in 1981, the year following my birth, came everywhere with me, thumbed so often the swirled cover detached. It is water-logged and ringed with coffee marks, years of underlines, layer upon layer.

I bought a CD box set in the 90s that featured a recording of you. There you were with your wild, husky voice, reading “The Truth the Dead Know” and “All My Pretty Ones.” I listened to you on repeat, and I can hear your voice in your words, even today: “My darling, the wind falls in like stones/ from the whitehearted water and when we touch/ we enter touch entirely. No one’s alone.”

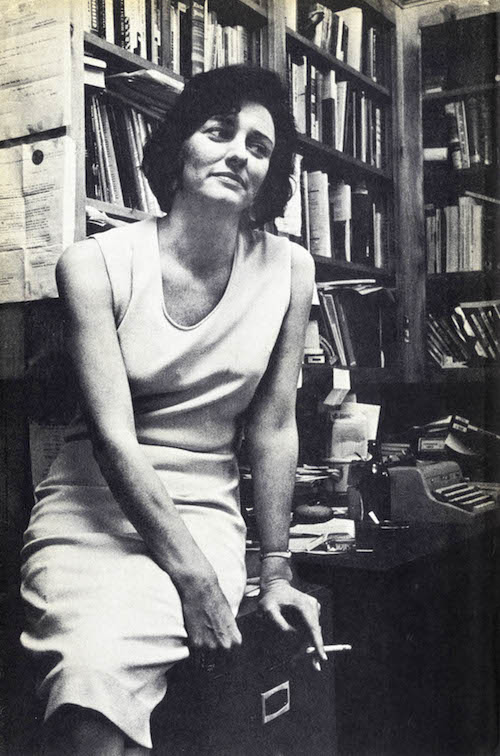

I became a smoker, maybe because of you.

I fell in love with the women I found in your pages—women I’d never seen before, revealed by the light you shone upon them. We needed that; I needed that. Those women, of course, were all around me as I became one myself. You taught me how to see them.

Next, it was your Transformations. These re-envisionings of Grimm’s fairy tales, with their “society-mocking overlay” as Maxine Kumin call it in the introduction, shifted the world for me. The lens turned, things I had not seen before—the fictive roles in which women are so often cast—came into focus. “Fictive” being the pertinent word here.

But how real fiction is! You knew this, as you wrote in “Red Riding Hood”: “Many are the deceivers:// The suburban matron,/ proper in the supermarket,/ list in hand so she won’t suddenly fly.”

Nothing, nothing, is as it appears.

I became a poet because of you. You, and Ani DiFranco, and because fiction, then, seemed too daunting. Your style was well out of fashion by the time I sat in college classrooms, sweating under the florescent-lit scrutiny of my peers. They did not care a fig for my excavations of emotion or my impossible longings or how I kept lighting bodies on fire, though they praised my brightness of language, my taste for color, and quibbled over my liberal use of em-dashes (for the record, they had nothing to do with Emily Dickinson).

But poetry always eluded me, or at least, the backbone I needed to continue making it in a world that received my words with only haphazard weariness eluded me. Perhaps this is merely an excuse for my not trying hard enough. Your mental illness and fragile emotional states are well-discussed, but to me, reading your books, all I see is a woman driven by her words—a woman not afraid of words on the page, which is more than I can say for myself those years I struggled to write.

I confess I gave up poetry, eventually, and turned to fiction. At first, my fiction was poetry. The chorus of workshoppers sang: where’s the plot? what’s happening here? why so much dazzle?

Dazzle, I declare, because language can be like a well-cut diamond catching the light. I think you, Anne, would approve of this, but that you would also approve of my—finally—diving deeply into the page. I had been skating the surface before, you see, I had been, still, afraid. Fiction, it turns out, made me brave. As brave as you? Maybe.

Words are still my first love, and for that I must thank you. But as a fiction writer, I have come to love structure and plot—something I can see now that you loved too. It is why your Transformations worked so well; it is why your poems worked so well—you had an eye for “that story.”

Story, I know now, transcends genre. Story is human. Story is us, all in it together, making sense of the world.

Yours, as ever, in spoons,

S

*

Post inspired by Grimoire Magazine‘s Dead Letters project.