What started as a simple post about getting lost in a book has morphed into a larger topic that I’d like to continue to explore, so I’ve decided to allow this to be a series. Part I lays some groundwork and asks some questions.

My mother says I learned how to read before I started kindergarten (not sure if this is apocryphal or not; I started K at age four1). We did not have books—or, a lot of books anyway—in our house, but I was taken to the small town library once a week. I no longer have my first library card, a battered little piece of paperstock, but I remember the layout of the library as if I were there yesterday: two rooms like butterfly wings off the main hallway, children’s on the right, everything else—magazines, adult fiction and nonfiction, what would now be called YA, reference, a card catalog—on the left.

The limit was five books. Somewhere in time—late grade school, early middle school, perhaps, based on what I remember reading—I started reading voraciously, usually devouring all five books before I went to bed the night we visited the library. I was reading The Babysitter’s Club and Sweet Valley Twins and Goosebumps. In those days I read mostly for entertainment, escape, and for the possibility of worlds other than the small town I knew. I didn’t judge myself for what I read; I read what I liked and if I didn’t like something, I didn’t read it. The year I was nine,2 we lived in Singapore for six months and there was a bookstore-lending-library, where you paid for the first book and then once you brought it back, you traded it for a different one, at no cost. How that worked as a business model, I’m not sure, but I loved that tiny shop. Those months, I read a series about three girls at boarding school—perhaps one of them had a French bob?—but I couldn’t tell you the name of the series of even the characters. Only that the covers were basic, and the person who ran the shop recommended them to me, and I read all of them.

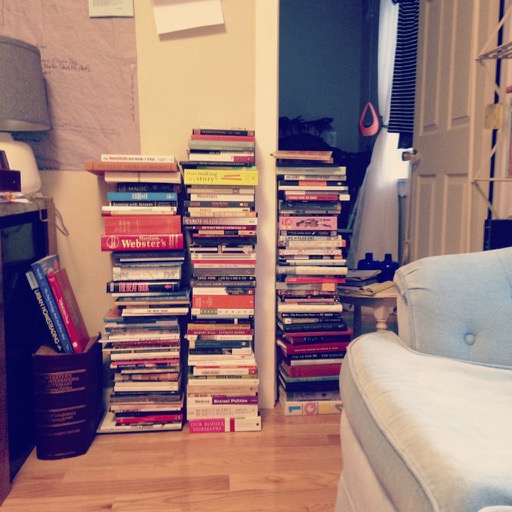

Even at my worst and lowest points, when life has felt completely out of control, I read.3 I studied poetry as an undergrad, then started a History PhD program and dropped out. I always bought the books on my reading lists, and I had a lot (my ex thought too many) books; in my late 20s I gave away at least half of my library and have spent much of my life since searching used bookstores for copies of Frankenstein and Six Wives with my name in the flyleaf.4 During the early days of the pandemic, I read constantly.5 I still do. I don’t watch tv and I don’t doomscroll. I do have a house and kids and a full-time teaching job. The few hour(s) I have to myself are usually alloted to reading. I annotate my books, I crack their spines, sometimes I tear pages out. Books mean many things to me, are many things to me, and symbolize many things to me.

I give this abridged reading history6 simply as evidence that I have been getting lost in books for most of my life.

Something I have noticed: there are different ways to get lost in a book.

❡

Another thing I have noticed: I get as lost in writing about reading as I do in reading.

❡

Not long ago, I picked up Nick & Norah’s Infinite Playlist. I saw the movie way back when (and again recently) but only read the novel for the first time in August 2022, while thinking about how to structure the Impossible Project. My copy came from Saver’s, a 1st edition from 2006, and already it seems like a little piece of history. I should say, I don’t read a ton of YA, and my first time reading—while I enjoyed it—I wasn’t blown away. (That’s okay, I am often NOT blown away.)

In January of this year, I picked the book up again. I’m not even sure why. But I read the first page, and then the second page, and then… well, since we’re talking about getting lost in books, it’s probably obvious enough what happened. I sat down in my reading chair and disappeared into the book. At one point, while reading, I paused to think and was made gradually aware that my husband and kids were playing Uno at the dining table behind me. They were in the middle of a game and there was yelling (we are not a quiet family) about reversals or almost winning or whatever and somehow I had been blissfully unaware of it all.

Because I was so caught up in Nick & Norah and their NYC adventure.

And I thought (not for the first time): How does this happen? How does a book keep a reader in a state of rapt attention?7

❡

Like many others in the blogosphere, I’ve read (parts of) Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Perhaps I don’t feel inclined to read more than I have because I agree with most of what is being said, to the point of wondering, Isn’t it obvious? The flow state is good, we should spend more time in it, art and community encourage flow, capitalism is diametrically opposed to flow. Also important: “Optimal experience is… something that we make happen.” Flow is meditative, but it isn’t passive.

❡

I go back and forth about getting lost in a book as being a flow state. Perhaps because getting lost in a book feels different from the flow that happens during a run8 or sitting around a table with friends or collaging or folding laundry or playing a game of Uno. Getting lost in a book is akin to leaving the “real” world and entering another world.

A world created by an author.

Something Ted Gioia (whose Honest Broker newsletter is one of the few reasons I keep a Substack account) wrote recently struck a chord: “A skilled musician guides an audience into the flow state.”9

Which I altered a touch for my purposes: A skilled author guides the reader into a flow state.

Thinking about books in this way of skills implies that craft has a large part in the process. And it does. The ability to write a good sentence, make well-rounded characters, establish and follow a plot, build suspense, create a mood—ALL these skills are very important.

It is also—and this is where I stumble to provide anything like an explanation—more complex than craft. I’ve read a million (at least a million) well-crafted stories that do not pull me into their world, that do not induce flow state. I struggle with reading a lot of “literary” fiction for this specific reason. (I’ve also read plenty of books that critics—readers and writers alike—bash within an inch of their life as poorly crafted and fallen head over heels. For example: Twilight. I read all four books in a week. Go ahead, judge me; I’d do it all over again tomorrow if I could!)

Clearly, there’s something more than craft that pulls a reader in; what is this something else?

Don’t get me wrong: Nick & Norah’s Infinite Playlist is a well-crafted book. But it has elements working for it that transcend craft, and those elements are what I want to explore.

❡

PART II — How Do We Get Lost (in a Book)?

❡

NOTES

- In contrast, both of my kids started K at age five—one very close to six—and neither knew how to read when beginning, despite living in a home full of books and being read to every single day of their lives. ↩︎

- 1990, in between fourth and fifth grade ↩︎

- Case(s) in point, my junior year of undergrad, living in downtown Manhattan post-9/11, I read (for class, but still) ~4 books per week. My first year out of undergrad, struggling with depression and a drinking problem and a broken heart, I read most of Virginia Woolf’s novels. ↩︎

- ala Serendipity: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0240890/ ↩︎

- Interestingly, in this case, even though it wasn’t long ago, I don’t remember much of what I read. During those first few months of lockdown, I was still drinking and the kids were small, and reading was more of a kneejerk escape method than it was an actual pleasure source. ↩︎

- If you want even MORE of my reading history, this post gets a bit more granular: https://www.sararauch.com/girl-canon/ ↩︎

- Perhaps there is a clue here, in that one must have rapt attention to give to a fictional world. ↩︎

- I miss running. ↩︎

- How We Lost the Flow ↩︎