Why are we drawn to what we’re drawn to?

What clues to the creative process might be revealed from our obsessions?

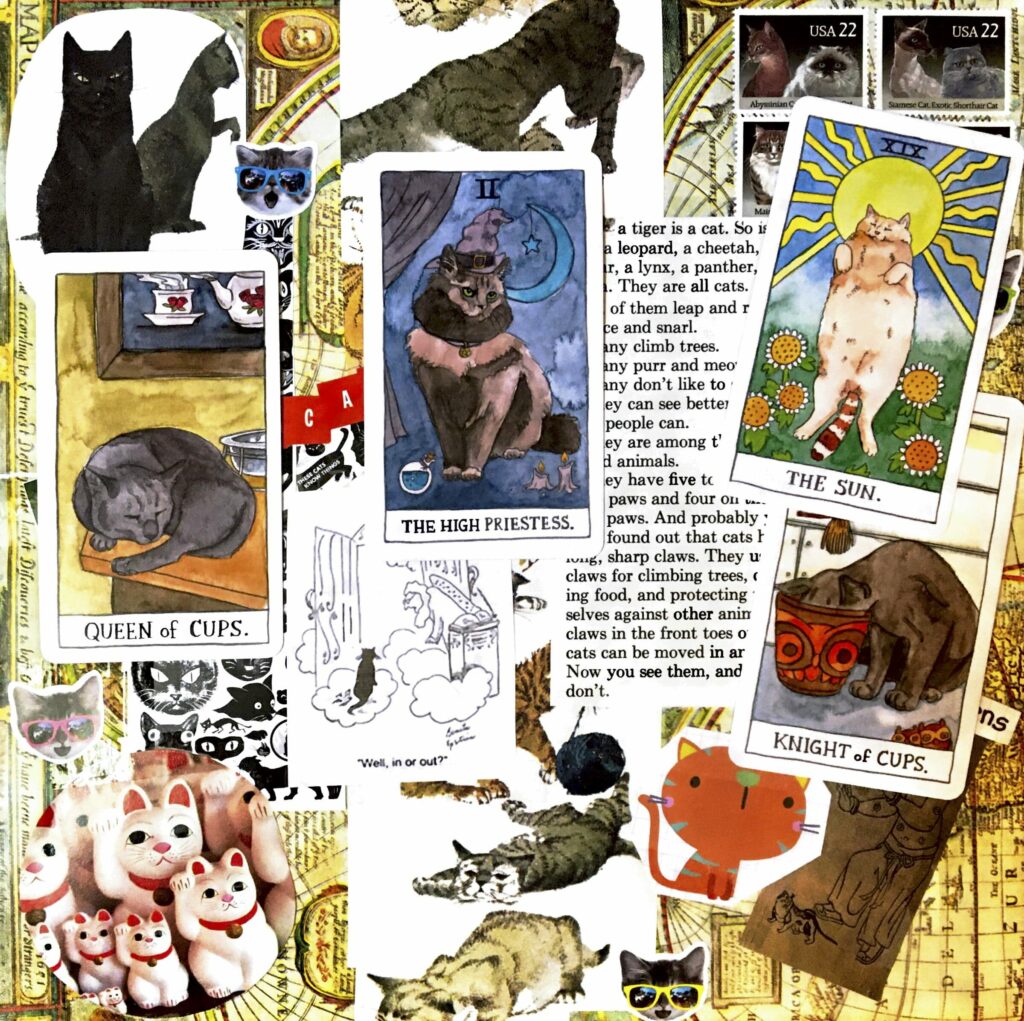

Can these obsessions yield art?

Here are the opening passages from a failed essay on cats (yes, I know):

In Milan Kundera’s novel Immortality, which I first read in 2004, there is a chapter titled “The Cat.” In it, a May-December couple who are experiencing a lull in their happy romance come together to go to dinner. The backstory lets us know that the young man has been taciturn and removed over school and work, and has withdrawn his affection from his lover, not out of spite or anger but pure distraction. While the woman dresses to go out, the man remains in the living room with her Siamese cat. He doesn’t like the cat, but he starts stroking the cat out of “duty.” The cat immediately bites him, and he is quick to anger, but the woman—who has seen the drama unfold—says, “’No, no, you musn’t punish her. She was completely in the right. … She demands that whoever strokes her really concentrates on it. I, too, resent it when someone is with me but his mind is somewhere else.’” This statement is, we know, a metaphor for how the woman feels about the man’s behavior—she “feels as if her other, symbolic, mystical self, which is how she thought of the animal” is serving as an example—the cat’s action allows her to see her own annoyance at her lover’s moodiness and withdrawal and drives her to “find the courage for a decisive act.”

I’ve never forgotten this passage, and (almost) twenty years later I can look back on it and formulate an understanding of how it impacted me: I, too, regard the cats I keep and the cats I write as symbols of my mystical self. My familiars, if you will.

Cats seemed an obvious enough place, for me, to start. Almost all of the stories I’ve written over the course of my life have featured a cat in some way or another; in fact, the death of my eldest cat last year is the opening scene in the book-length essay I’ve been working on during the pandemic (published in 2022 as XO). The essay is about much more than my cat, and I hadn’t planned on including his death in the manuscript until, well, he died. His death opened some portal into a place I’d long been scared to investigate.

Despite the fact that cats are one of my obsessions, and also some kind of creative catalyst, most people who read my work would not – I’m guessing – say it’s about cats. Nor would “cats” be a theme that came to mind when I rattle off the themes I’m writing about.

But, when I started thinking about why I’m drawn to cats, and what might lie beneath this curiosity, I started doing some research. Here’s what I discovered:

The earliest known records of cat veneration show up in Ancient Egypt, in the veneration of Mafdet, who resembled a cheetah, and Bastet (2nd millennium BCE), who appeared as a cat or a feline-headed goddess. But as Yekaterina Barbash notes, “Egyptians did not worship felines. Rather, they believed these ‘feline’ deities shared certain character traits with the animals.” In this subtle distinction, there’s space to investigate how humans transsubstantiate the natural world into a spiritual realm. From here, we can learn something about how we tell stories and make meaning of the world around us.

For many of us, religion provides some of our first experiences of storytelling. Alongside Mother Goose’s Nursery Rhymes and Aesop’s Fables (morality plays, all), attending church, synagogue, mosque, sweat lodge, prayer circle, etc., centers us directly in communal stories. In these stories, we find cultural mores, societal dictates, moral instruction. We also—and this is the part that I fear we, as a culture, are losing—find magic. Transcendence. Intrigue. Fascination. After all, for stories to impart any kind of knowledge, they must first hold us captive.

The cat goddesses of Egypt embodied a fierce, lithesome grace that the Egyptians deemed essential to being (also essential: keeping rodents out of the grain stores)—and so these physical feline traits were given a mythic, immaterial form. In this way, they were kept alive—and significant—in the culture’s systems and imagination.

In essence, what cats embody, for me, in life as on the page, is mystery. And mystery, that great chasm between what we can know and what we cannot know, is the very reason I write. I don’t necessarily want to find the answers. But I do want to engage with the questions.